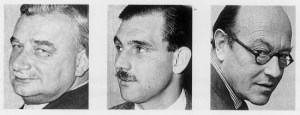

The original CDP trio…with John Pearce far right

As the 50th anniversary of its foundation approaches, our series paying tribute to ad agency CDP continues.

The only one of the founders to play a long-term role in the famous ad agency Collett Dickenson Pearce was John Pearce. There were many enormously influential people at Colletts in the earlier years – Colin Millward, John Salmon, Alan Parker and of course Frank Lowe – but without John, none of it would’ve happened.

He probably had the most amazing cv in post-war UK media. A former editor of Picture Post (he once fired the legendary liberal journalist James Cameron) Pearce also founded the Eagle comic with Marcus Morris – as well as inventing the cartoon character Harris Tweed. While serving as a leading light at the Tories’ agency Colman, Prentice & Varley, he sold the famous line ‘Life’s better under the Conservatives – don’t let Labour ruin it’.

Although a fervent supporter of great creative work, John once told me he had two golden rules in life: never use your own money (“that’s what the f**king banks are for”) and never give management power to creative people. This latter was not meant as a slight: he simply felt creative people should create, and leave management and selling to those better equipped to do such things.

If not life-rules, he did also have very strong beliefs about what made for a great ad agency: independence, culture, creative talent – and selling a campaign first time. Independence, he felt, brought firmness with clients: for this reason, he bought the agency back off the stock exchange after a few years. Culture was vital: everyone had to know why they were working at CDP, and above any other, this was a cornerstone that Frank Lowe recemented into the building every day. Creative talent was not just based on money, but also on doing ads that would make every great creative want to work at CDP. And selling ideas first time meant you could get by on ten brilliant creative teams rather than twenty…because starting again from scratch could be kept to a minimum.

This last dominated his outlook. John absolutely hated having to change anything at the client’s bidding – but it was almost entirely commercial nous rather than creative truculence that led him to feel that way.

I once attended a client meeting with JP where a brand we’d initially launched in a very upmarket role had over time become more mass market. We’d been doing classy colour press ads in posh media like Horse & Hound, The London Gazette, Tatler and so forth. The campaign has been showered with awards, and the media buying ran itself – but the client insisted we should be switching to more downmarket (C2) titles.

The truth is that John instinctively knew how seeing the ads in the context of the titles we were in would always impress aspirant users; but in a moment of pure ironic genius, he gave this speech to the astonished marketing director:

“Well, we all know what C2s are, what? They’re malingerers. Where do you find malingerers? Doctor’s waiting rooms. What do they read in doctor’s waiting rooms? Horse & Hound, Country Life, Tatler etcetera…what? No need to change the media plan at all”.

And that was that. I think this was the high-point of my advertising career.

Pearce’s habit of saying “what?” at the end of every sentence was not an affectation: he really did go back to the Wooster era, and often dropped the ‘g’ off words like ‘fishing’. Somebody once said to me that the formula for advertising success was good teeth and a winning smile. If that was true, then John started out with major disabilities: his teeth were informally arranged and stained in nicotine, and his smile was disturbing enough to make Gordon Brown’s seem engaging by comparison.

No, John Pearce didn’t schmooze clients: he impressed them with the power of his personality – and his track record demanded respect. Clients came to CDP because their brand was in trouble, and needed a famous campaign to rescue it. Over time in the 1970s, Ford, Silk Cut, Fiat, Cinzano and many other big names came through the doors desperate for a bit of pixie dust – and got it. John insisted on good manners at all times, and adored clients who believed in the Colletts philosophy – but he was no respecter of reputations.

In the Spring of 1976, the ICI brand Vymura asked us to pitch for their business. ICI then was like Microsoft now: they didn’t come any bigger. We were doing a last rehearsal before the pitch when JP wandered into the presentation, and had this conversation with Geoff Howard-Spink:

JP: What you doing?

GHS: Preparing a presentation, Chairman.

JP: Why?

GHS: Because ICI are coming in this afternoon.

JP: What do they want?

GHS: Er…I assume, they might give us their business.

JP: Do you? They might just want to borrow a fiver.

And with that, he wandered out again.

Mr Pearce (as he always was – or ‘Chairman’) had a soft spot for me because I’d once defended the Hamlet campaign against the attentions of a new client out to make his mark. He never forgot this. And I will never forget him.