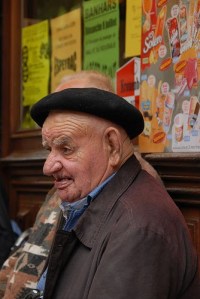

Every one-horse town and village in France has a Starer. You have to be about 80 to get the job, and you have to be male. Females dressed in twenty layers of clothing on doorsteps during a hot summer’s day also stare at every stranger passing through, but they’re different: they’re old women, and thus nosey. Without being nosey, how else would they know what their husbands were up to?

The town starer isn’t there to be nosey about folks driving down the main road. His job is to decide whether you’re up to no good, foreign (and thus very likely to be perfidious) or a French stranger – but OK despite that. He gets elected by being a renowned judge of character, so his unwavering stare is designed to suss you out. He’s not some gossipy old fishwife: he’s the Jury.

The Starer in our village sits on the same bench by the old disused Cafe de Commerce from March 31st to October 31st every year. This has (ever since we came here twelve years ago) afforded him a perfect Starer’s view down the straight road through this run-down settlement. To the left of his seat is a tight right-turn bend, thus enabling him to observe speed, care taken, number-plate, facial features and other signs of character – or lack of it. On arriving in any French rural town in search of a murderer, any self-respecting member of the surete must first see the Mayor, and then ask politely to see the town starer. (This never happened in Maigret novels, because Simenon wanted his hero to be superhuman in every way).

Anyway, after five years of being stared at, one day after leaving the bakers I walked over to him, offered an outstretched hand, and wished him bonjour. His face cracked into a broad smile, and he wished me the same in return. He never gaped at me again: I had passed the exam – I was un bon type.

This year he’s not there. He’s probably just indisposed, because there’s no new starer in place. On the other hand, perhaps they haven’t held the election yet. But if a new occupant of the peeling and rickety bench appears, then we shall know for certain that he has gone to look down upon humanity from a more celestial vantage point.

The reason our town is so dishevelled is interesting – although I didn’t find this out until a couple of years ago. Our area is what was Vichy during World War II – that is, it was French run, and only German occupied with a light tough. A ‘light touch’ to the Germans involved having just the one Gestapo torture-chamber in town, as opposed to three. It seems that our backwater was infested with collaborators….those who took the Nazi Reichsmark – and shopped comrades, or shagged the Wehrmacht.

It is virtually impossible here – seventy years later – to get a conversation going about the Occupation. A mixture of pride, shame and embarrassment has created this wall of silence. But apparently, the local Prefecture’s revenge for some sixty-four years was to deprive our town of any State funds for public restoration and improvements. Three years ago, this changed: we now have a new Mairie, improved street lighting, and decorative flowers – plus sleeping policeman in the road at either end of town. The time had come to forgive and forget….especially as all those involved had been dead for donkey’s years.

Whatever the local history might suggest, there were some exceptionally brave Frenchmen here during the German Occupation. I met one such (through Dutch friend Leo) about six years ago. He was 93 then, and still active as a mechanic. He took me for a spin in his self-restored MGB GT sports car, and I don’t know what he’d put under the bonnet, but it was no respecter of speed limits.

He’d been De Gaulle’s chauffeur during 1940, and driven him down to the West coast, where the French Government hastily reassembled after the fall of Paris. De Gaulle spent the morning trying to persuade Laval and the other traitors to continue the struggle against Hitler. Having failed to do that, he returned to the car and told the chauffeur to drive him to a nearby beach. There, a French seaplane took him to exile in England.

Our local celebrity drove the car south until it ran out of petrol, then changed into civilian clothes and walked the rest of the way home – some two hundred kilometres. He joined the resistance, and spent the next five years blowing up anything German.

He died soon after I’d been introduced to him, which was a disaster for him but also a great loss to me. He had a zest for life that I can’t describe: as they say, ‘you had to be there’. This is still a chemical nobody has even identified, let alone isolated. A large part of me hopes they never do.